January 2026 Update:

The software from this project has been ported to the new Pebble watch here. Source code for the Pebble watchface is available here.

Source code for the custom smartwatch project has been open sourced here.

I’m also proud to say that these two watches are still kicking after a year of school, summer vacation and two little league seasons - and haven’t needed a single software update ;)

Background

My 9 y.o. son has Type 1 diabetes, which basically means his pancreas is on manual (hard) mode 24x7. A healthy pancreas not only produces insulin, which helps convert glucose in the bloodstream into energy - it also produces glucagon, which tells the liver to release glucose into the bloodstream when blood sugar levels are too low. A person with T1D has to manage without either of these guardrails, and a low blood sugar can become a medical emergency if left untreated.

We’re lucky to have access to life-changing technology like CGMs and Closed-loop Insulin Pumps, however, they come with their own problems, such as the alarms that go off during a high or low blood sugar. My son’s pump and phone both alarm when he falls below 55 mg/dL. This can happen very quickly in a number of situations - such as if he’s just had lunch, just had a large insulin dose to cover it, and recess afterwards. There’s also playing at the playground, or playing soccer, where he shouldn’t have to run around with a phone strapped to him - but ideally he should also be developing a sense of when a low is going to happen, and catch it before he’s about to pass out.

Another important point is the number of times someone with T1D (or their caregiver) checks their blood glucose data throughout the day. It’s kind of like having an unfinished task in the back of your mind all day every day - which can create fatigue and burnout. So if I could shave away a couple seconds or some of the effort to check - or even better, have a haptic alert at the right moments so you don’t even have to check at all - that could add up to a big quality-of-life impact.

“Why Don’t You Just Buy an Apple Watch?”

This is probably what you’re wondering. There are a couple reasons why. First, the Apple Watch (like all Apple products) is too much device for a kid. It ships with so many shiny features and apps and notifications. It’s a beautifully crafted marvel of design and engineering. It’s also way too distracting for a kid while they’re at school. Secondly, it doesn’t provide a good, reliable view of his CGM data. The Dexcom integration is often backgrounded, doesn’t show the chart in the complication, only the number and an arrow. People use hacks like creating calendar events just to see up-to-date data.

And the iOS settings, Screen Time, and notification systems have ballooned into a giant ball of complexity. What we need is something simple.

This is the argument you will have whenever you try to build something that might improve on something already in market. Just because a thing exists in market and checks a box, doesn’t mean it works very well. I surveyed the Type 1 community about this idea, and the results suggested that I wasn’t alone - that while these devices exist and some people use them, the responses indicate that they don’t work very well.

"This is awesome! We were just talking about looking for something like this with basic functionality for my son without having to get an Apple Watch!" - M., T1D parent

"This is a great idea. Most smartwatches available have too many extra functions (distractions) for a child. This is pure simplicity and to the point." - B., T1D parentAnd Apple talks a lot about designing for kids and providing safeguards, and they do have people working on those things - but fundamentally, Apple is not a Public Benefit Corporation. These devices are designed to be addictive, to keep people drawn to them. That isn’t something I want my son to have on his wrist while he’s at school.

So for a while I’ve been toying with the idea of building a simple, single-purpose smartwatch for my son, with the thought of trying to take it to market as a consumer product. Another T1D dad/product designer I know, Matt Lumpkin, worked on a similar idea back in 2018 and wrote about his experience. His written case study and presentation, along with his input and encouragement when I reached out about it, gave me the confidence to push ahead with this project.

"In our survey of over 100 cgm users we found that not one of them had not suffered some negative impacts on their relationships and social life due to CGM alerts, alarms and notifications." - bgAware case studyIn the end, after 6 months of work, I succeeded in building a small run of working prototypes that my son and I are still wearing today. But I wasn’t able to find a viable path beyond that milestone. With the details still fresh, I wanted to document and share my experience in case it helps others or proves interesting to anyone else considering hardware R&D.

I should note that I’m a software developer by trade that is new to hardware and electrical engineering. I’m sure that a lot of what I write about and what I discovered along the way are painfully obvious to professionals in this field.

Product Requirements

My design goals:

- something simple, no bells & whistles that would distract my son during school, that didn’t require a ton of effort to configure

- that would stand up to playing on the playground or baseball/soccer field, and survive the occasional rainfall or splash

- that would pass for a real consumer smartwatch

- that provided reliable CGM data on demand

- that provided haptic feedback at important moments like “urgent low BG soon” and “high BG for over an hour”

- watch faces that potentially gamify the process of checking one’s BG, or at least make it feel less clinical

Process

I could break the project down into functional parts like electrical, mechanical, software, final assembly, but it’s all interconnected, so I’m going to try talking about versions instead.

Early Breadboards and Modules

A year and a half ago, I tried programming an off-the-shelf device called the M5Stick to display CGM data. It worked! But the battery life was short, it was using WiFi, and while the case was a cool orange color, it was bulky and wouldn’t protect the electronics inside from rain or even careful hand-washing.

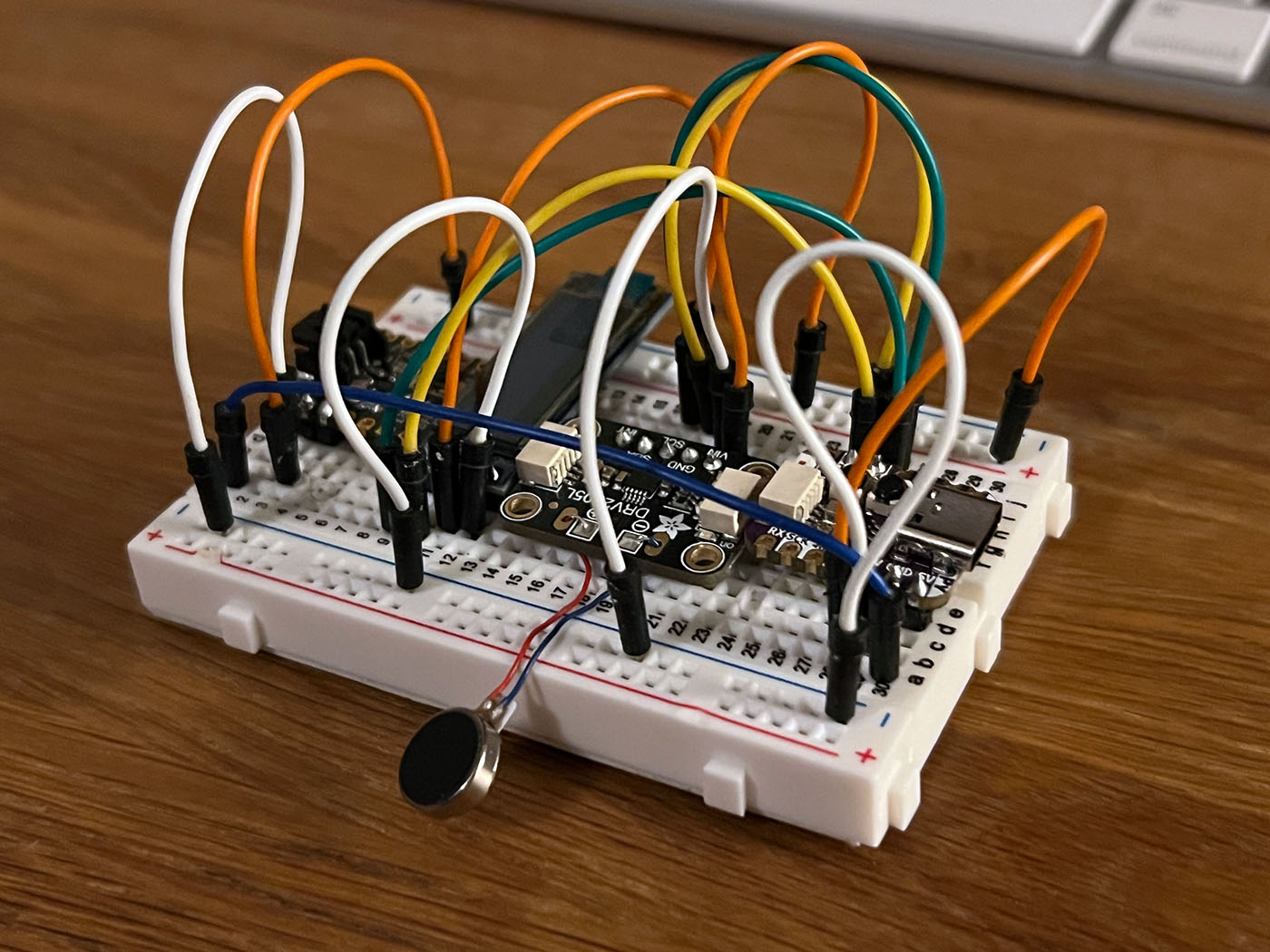

Once I was working on this in earnest, I started out using off-the-shelf modules from companies like Adafruit and SparkFun, which provide breadboard-friendly modules for MCUs, sensors, batteries and buttons, along with really helpful documentation, tutorials, and even schematics and PCB layouts. This allowed me to work on critical paths of the Arduino software and connect all of the main parts together with minimal soldering.

The First Big Hurdle: A Reliable BLE Connection

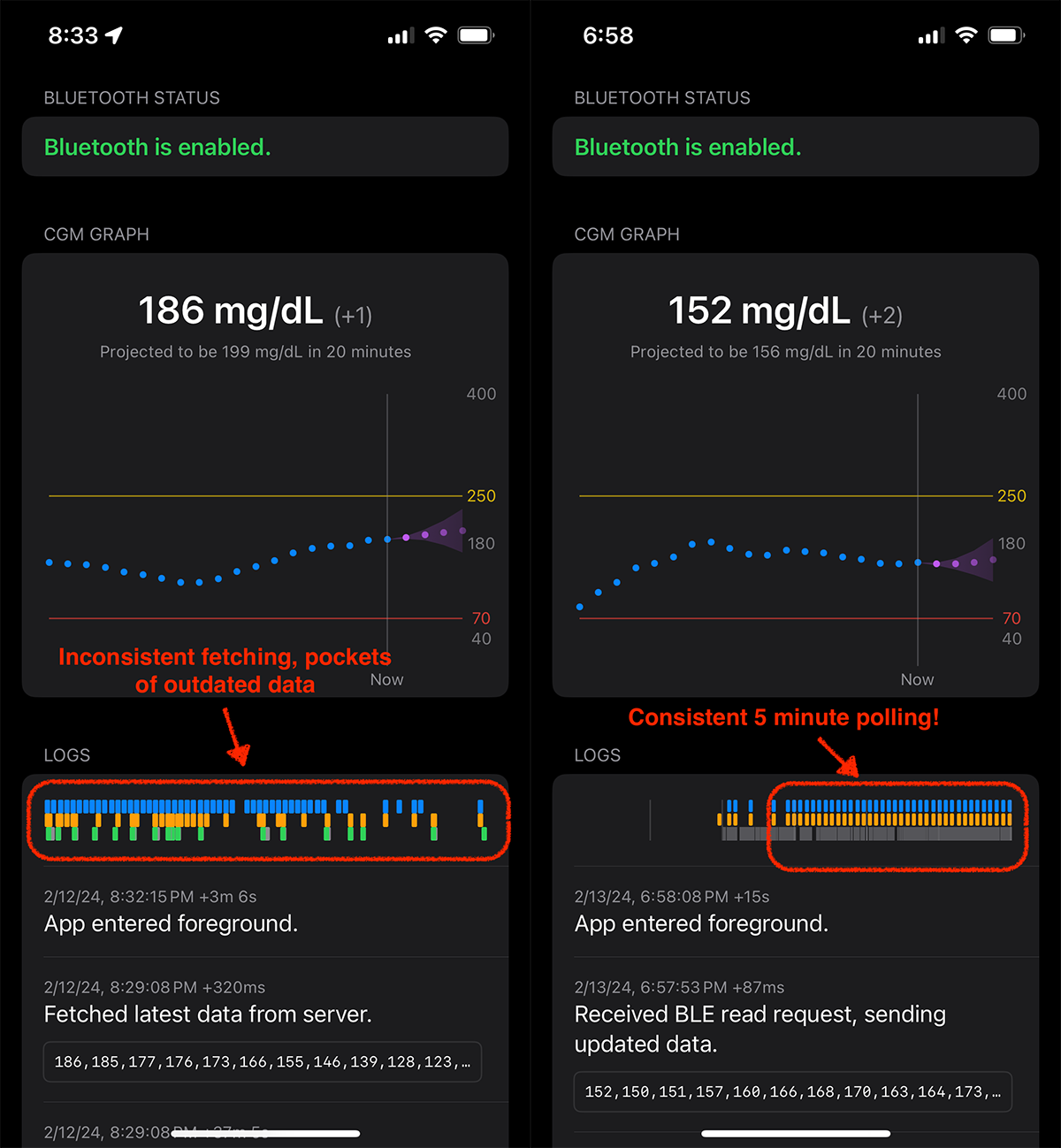

Throughout the project there were big technical question marks that I knew could end the project if I couldn’t figure out a good solution to them. The first one being a reliable BLE (Bluetooth Low Energy) connection to a companion iOS app, which would pull down the latest data from the Dexcom API. Apple makes it very difficult to do what you want to do, when you want to do it, in the name of preserving battery life and keeping the device and its other processes running smoothly. I initially tried having the iOS app to schedule a background task every 5 minutes to fetch the latest data from Dexcom. It worked great, as long as the iPhone was plugged in and the app was foregrounded. But as soon as it was unplugged, or backgrounded, the scheduled task sunk into a fog, only occasionally reappearing. As far as I could tell there was no way around this. Apple also references a lot of opaque heuristics that consider how often the app is open and in use, how much battery life is left, what else is happening, and all of that changes over time as the OS learns more about usage.

This nearly ended the project. Fortunately, what ended up working was making the smartwatch the peripheral that wakes up every 5 minutes, connects to the iOS app and performs a BLE read request, and not only will the iOS app (almost always) reliably wake up, it has time to make a HTTPS request during that BLE read request. So I had my proof of concept of reliable BLE -> HTTPS connections.

Even better, because Dexcom’s CGM data follows a predictable time interval, I was able to get the watch to time its wake-up and BLE read request to happen just a few seconds after the latest value was uploaded, so the watch was never more than a few seconds behind the sensor or pump.

Making the Jump to Custom PCB

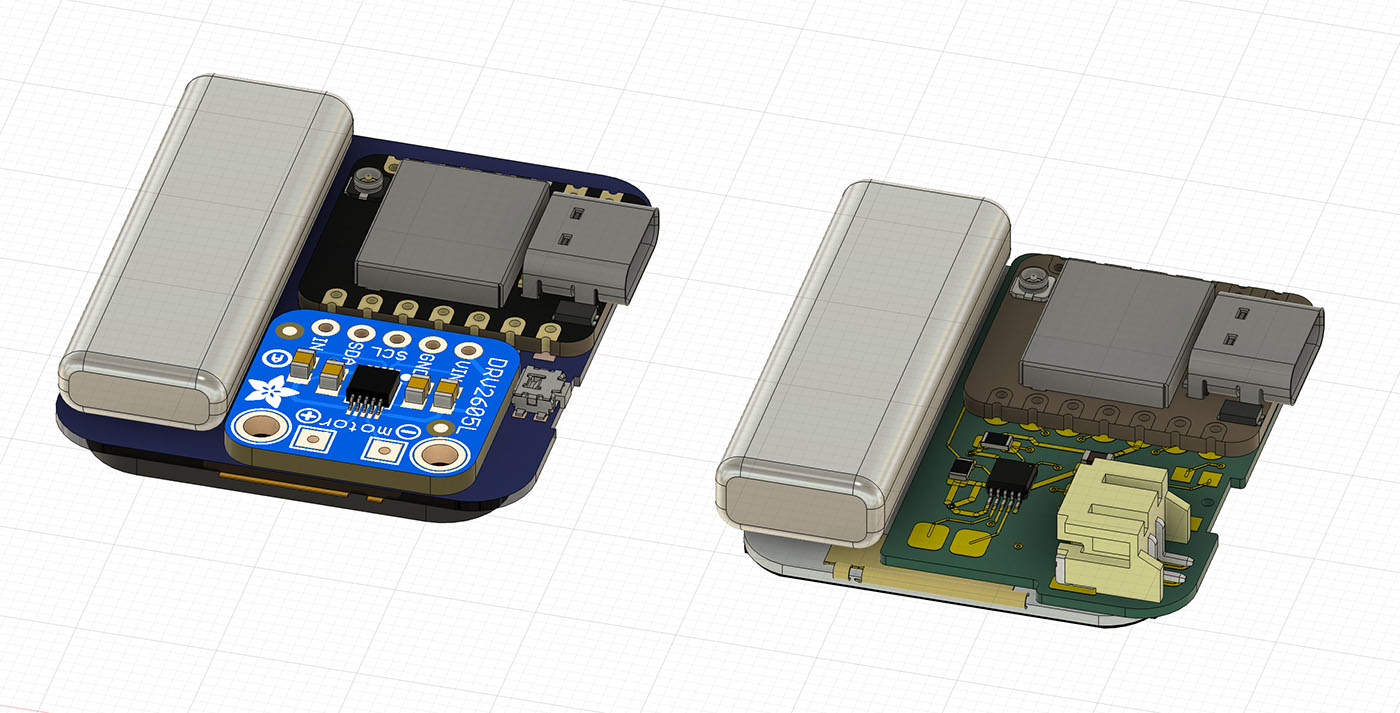

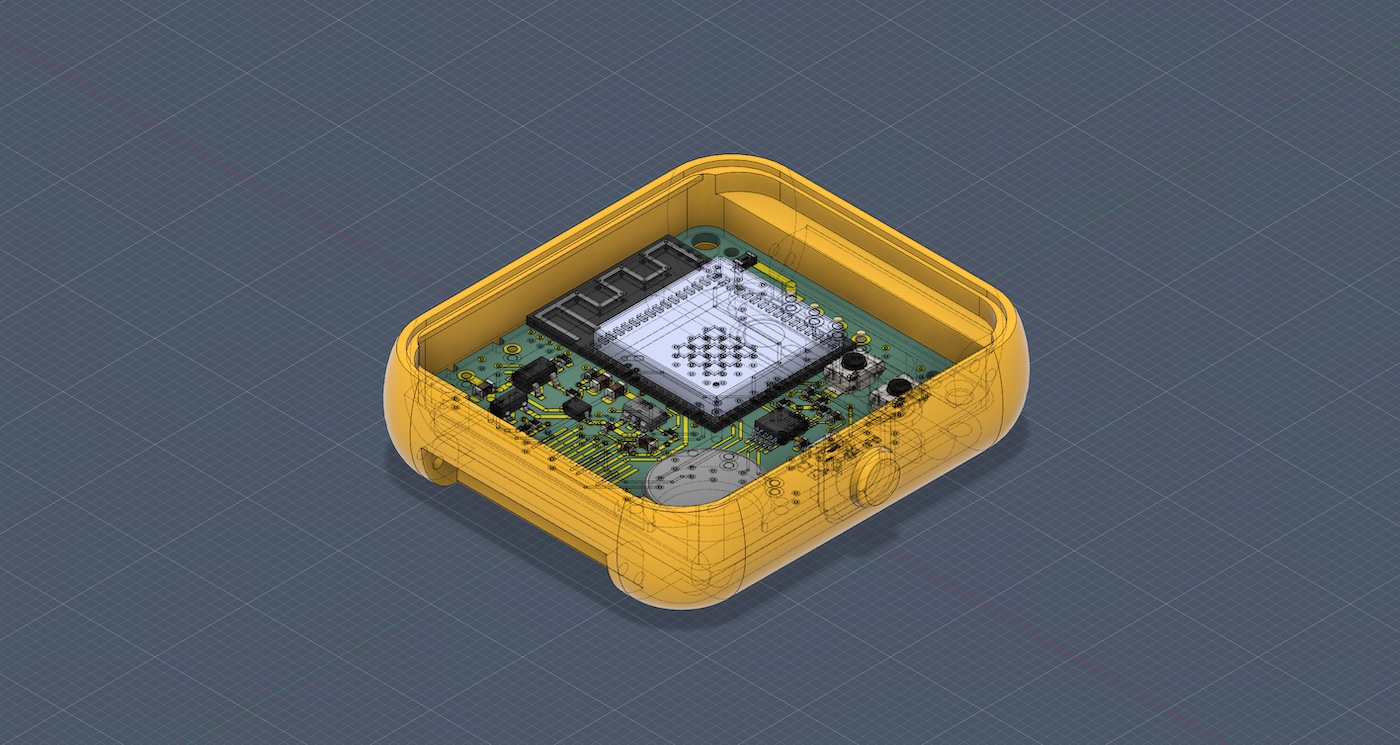

With a breadboard proof of concept complete, I started working on how to make this small enough to fit into a case. I learned the 3d modeling program Fusion 360 by Autodesk. This was a bit head-spinning because it required thinking and working procedurally. So instead of drawing a 3-d box to start, you start with a 2-d sketch, and then extrude that into a shape. Edits to the 2-d sketch (which is now further back in the timeline) will affect the extruded shape, and any other changes in the timeline. It was easy to get into a weird state, so it’s important to follow a careful order of operations in Fusion 360.

Once I had all of the modules and parts in the program, it was clear that I would need a custom PCB to miniaturize everything down to fit in a watch case.

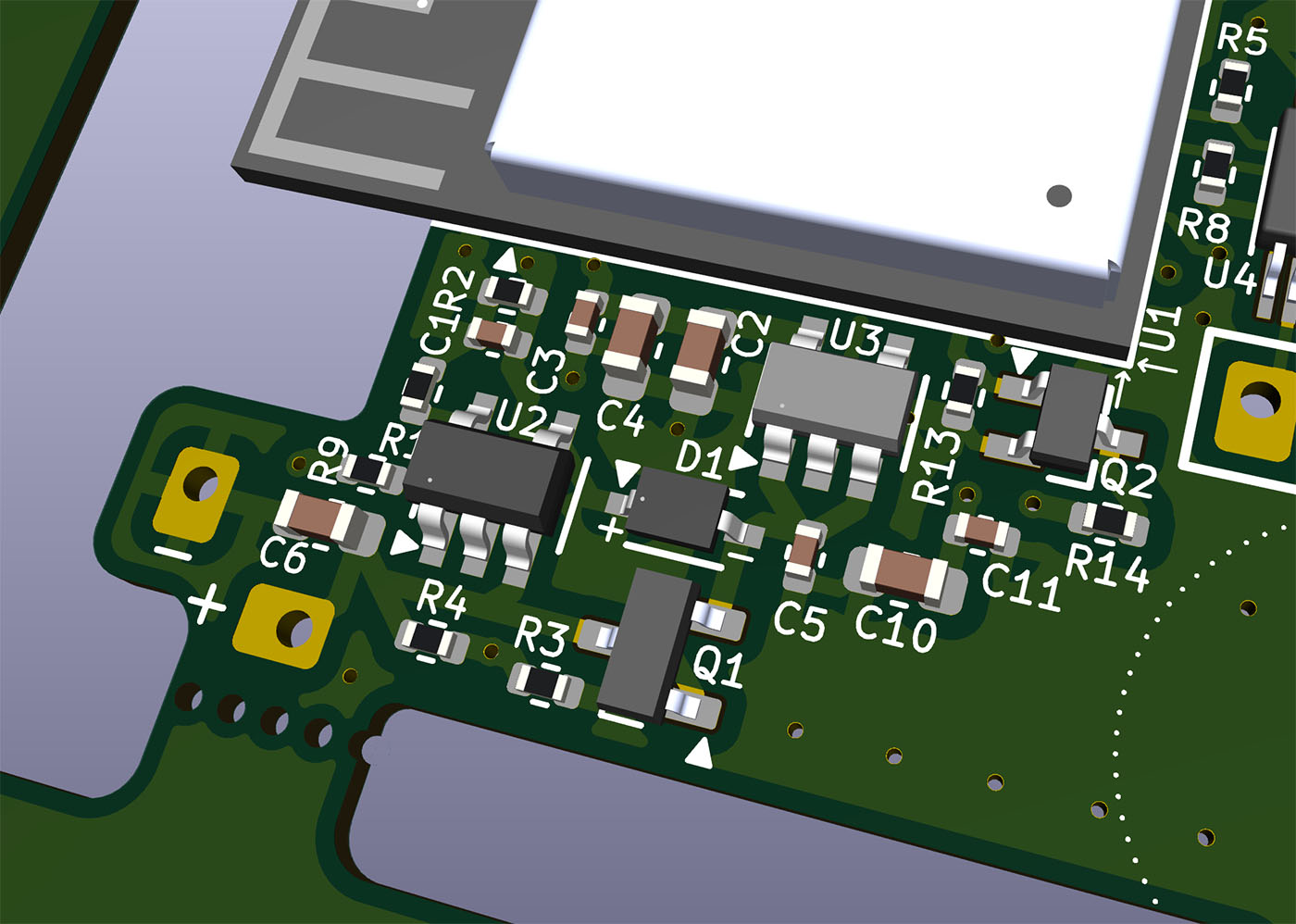

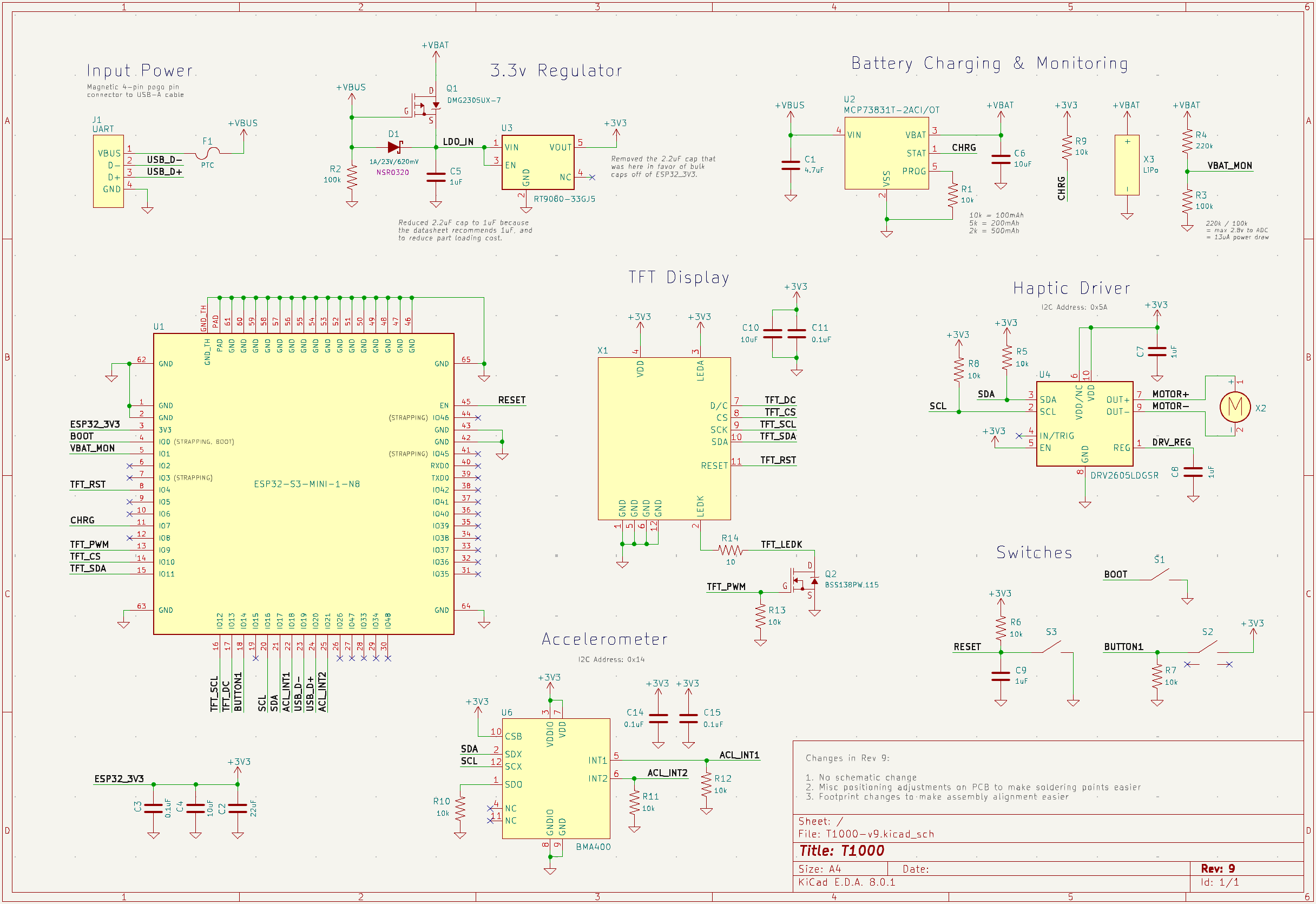

This was a big step for me. It required learning electrical engineering fundamentals, schematic and PCB design software (I chose KiCad, and have been happy with it), and how to package it all up in a way that a PCB fabrication house would accept, and then would actually work once I have it wired up. I learned that designing the PCB layout was the last step, not the first, and most of your time would actually be spent building the schematic, sourcing parts, reading datasheets, and preparing the part symbols, footprints, and Bill of Materials.

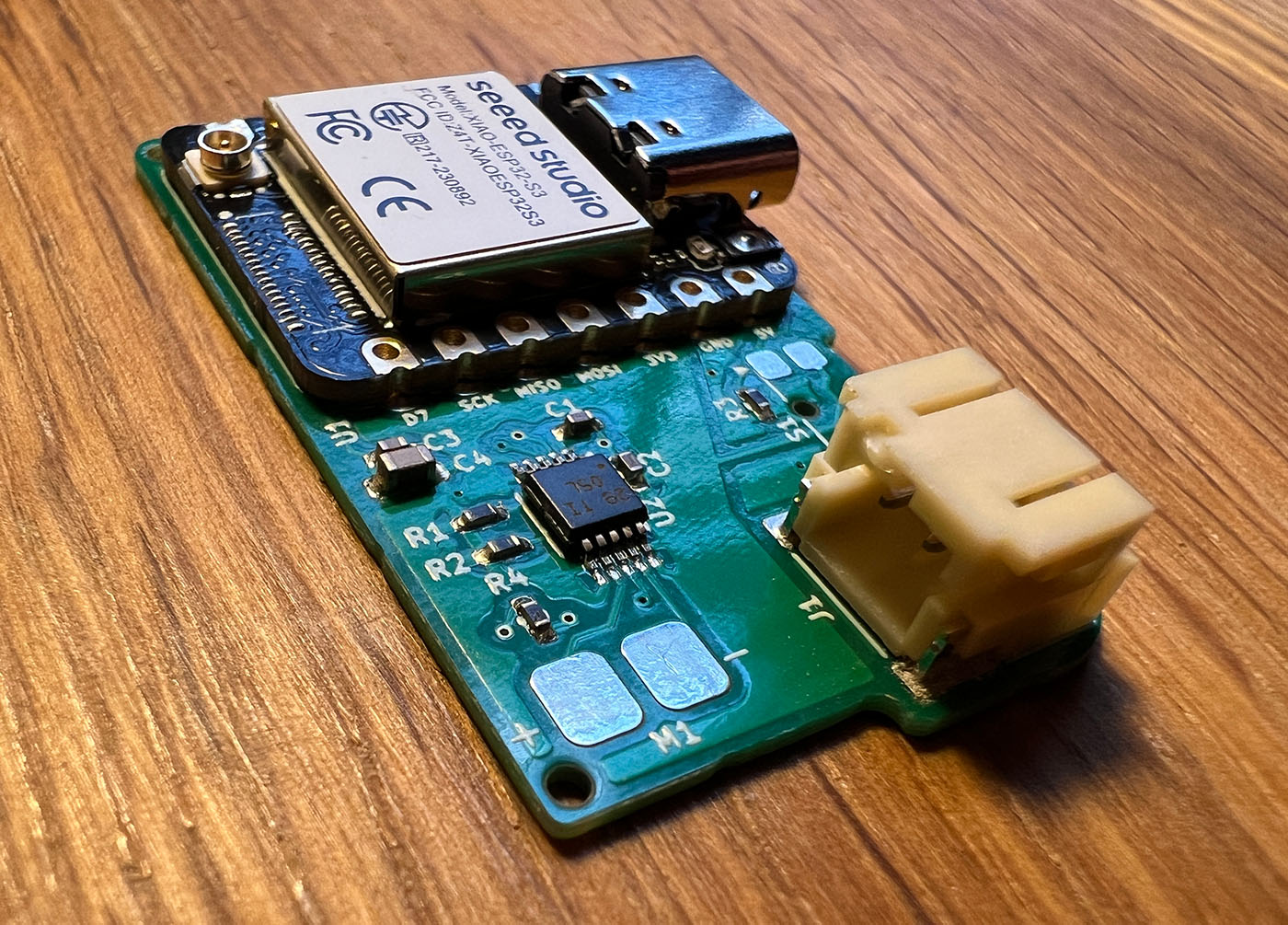

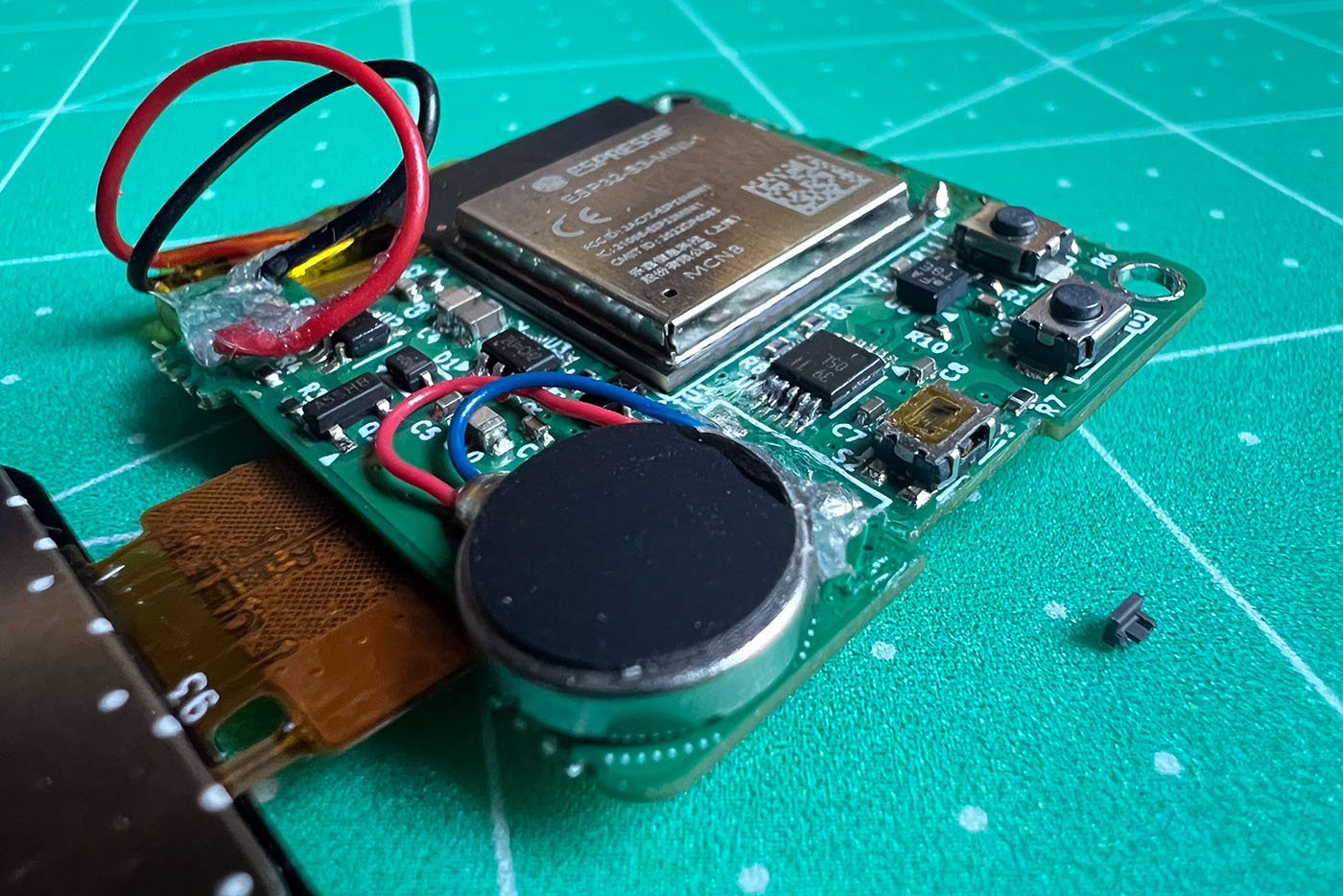

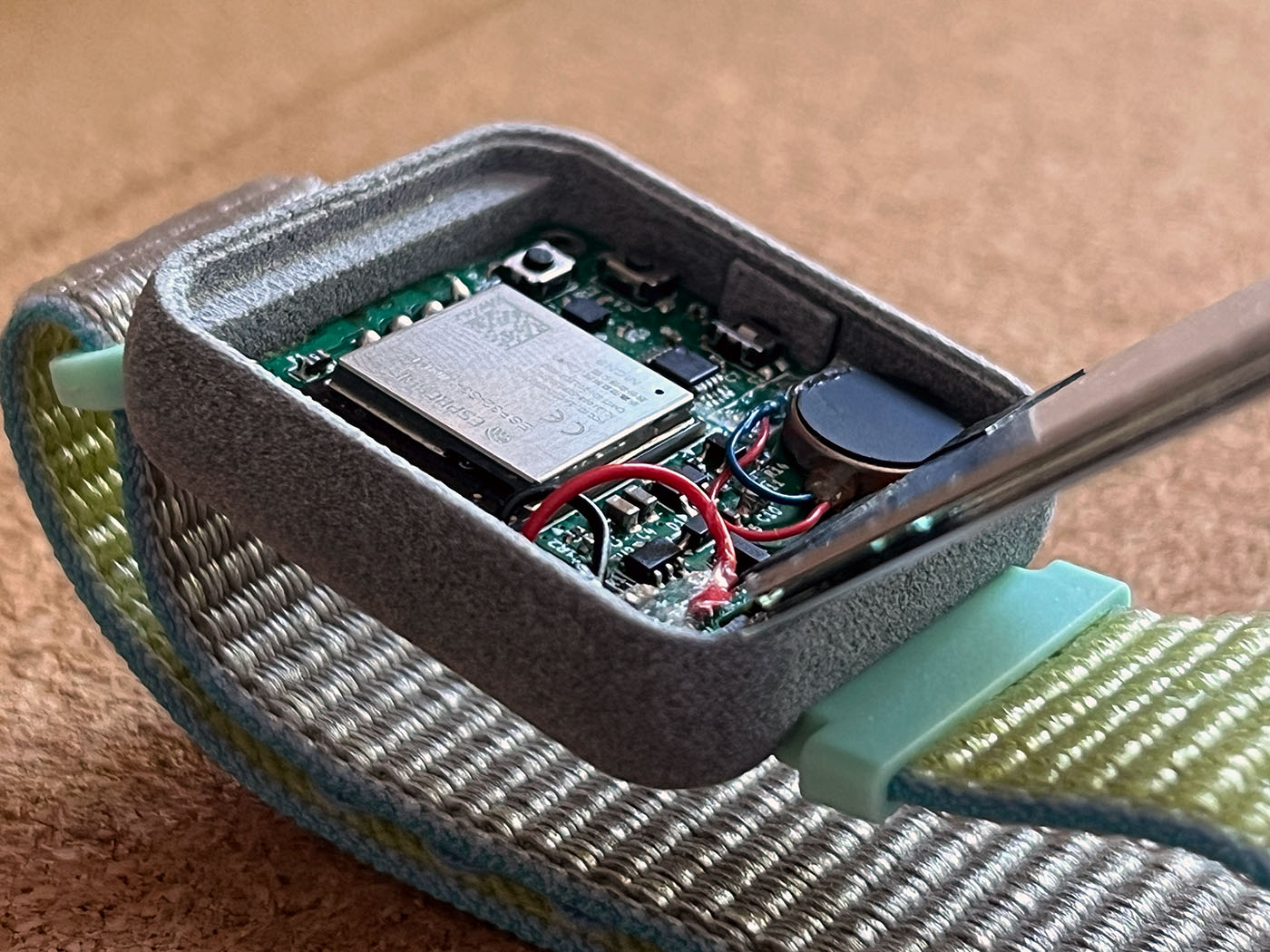

After a lot of time and effort, my first PCB arrived! I now had the battery connector, button, and DRV2605 integrated on a single board.

I soon discovered that I had reversed the polarity of the battery leads on the back of the ESP32-S3 module, so it wouldn’t power on. Woops. But despite that, I was feeling confident enough to drop the ESP32-S3 module I was using and place the chip itself (specifically the ESP32-S3-MINI-1 which includes an integrated RF antenna) directly on the PCB. To do that, I needed a way to connect the PCB to my computer so I could flash the firmware and create a serial/debugging connection. In researching other devices on the market, such as the Bangle.js Watch, I realized the easiest way to go about it would be using magnetic pogo pins. I found a supplier of 4-pin connectors that also sell 4-pin pogo-pin to USB-A cables, and they’ve worked well.

Around this time I worked with a local 3d printing shop and had them print a few case designs for me using resin. The prints were perfectly accurate, but proved to be brittle and wouldn’t hold up to actual use. I also learned the hard way about the importance of adding tolerances, or space between parts that were meant to fit next to each other. My first version had no tolerance, and I broke the case trying to force the pogo pin head in. After that, I found that 0.1mm worked well for press-fit parts.

Surprise! Haptic Motors Are Finicky

You might think that haptic coin motors would all work the same based on their stated performance, but they don’t. The resistance between one coin motor and the next meant that the voltage requirements and actual performance can vary from “nothing at all” to “extremely loud”. It’s possible to calibrate the DRV2605, but I found that the only way to get reliable performance out of the motors is to only use ones that had similar resistance of around 30 ohms.

There are also two basic types of haptic motors: ERM and LRA. ERM motors are basically just vibrators, whereas LRA provides a much more subtle range of feedback. Apple’s “Taptic Engine” uses LRA. I found that the LRA motors I could source were not loud enough to register - it could’ve been a number of factors, but I stuck with the louder and more simple ERM motor for my prototype.

Part of the idea for alerts was to provide not just a buzz, but a series of quick taps, at a speed relative to the blood glucose trend. So if the trendline is low and going down, it will tap fast and speed up. If the trendline is low and going up, it will tap fast and slow down, and so on.

// Play a beat based on latest BG value and velocity

void playSugarBeat(float bg, float vel) {

float totalDelay = 0;

float maxDelay = 3000;

int maxBeats = 8;

for (int i = 0; i < maxBeats; i++) {

// 40mg/dL = 20ms, 400mg/dL = 920ms

float multiplier = 2.5;

float offset = 80;

float bgToDelay = (bg * multiplier) - offset;

totalDelay += bgToDelay;

if (totalDelay > maxDelay) {

break;

}

playEffect(1); // 1 = a short tap

delay(bgToDelay);

bg += vel;

if (bg > 400) {

bg = 400;

} else if (bg < 40) {

bg = 40;

}

}

}After a few days of testing with this algorithm at alert-worthy moments, I found that I had developed a pretty good sense of my son’s BG without needing to look at the screen.

Display Options

I ended up using a 1.69” 240x280 pixel TFT IPS display. I would’ve liked to experiment with an AMOLED, E-ink, or the e-paper/MIP LCD that the last Pebble watch used, as they offer much lower current draw, the AMOLED offers higher resolution and a much more vibrant display, and the E-Ink/e-paper both offer an always-on display. Unfortunately, these displays were much more expensive, and I wasn’t confident that I would be able to use an existing display driver library (such as LVGL or what I ended up using, TFT_eSPI) to program them.

I didn’t include a touchscreen, because I didn’t want to complicate the project or add an additional layer or glass and circuitry and make the watch even thicker. Keeping it simple is part of the point.

Case Fabrication and Finish

I worked with a company called Fictiv to fabricate the cases. Fictiv provides a lot of different materials and process options, an immediate quote, and is there should you graduate to medium or large-scale fabrication. I found them to be quick, affordable, and reliable.

There is an overwhelming number of process options, and within each option are another overwhelming number of material options. I tested out Selective Laser Sintering and Multi-Jet Fusion. MJF was the winner: it’s affordable, the prints were extremely accurate, the nylon material very durable even when I pushed past the 1mm minimum thickness recommendation, and it has this satisfying, random, grainy surface texture. SLS seemed durable, but the print resolution was a little rougher and it had a more obviously 3d printed look to it. The only problem with MJF is that it’s porous, so water will seep right through it. I needed to find a professional looking coating. I tried hand painting, airbrushing and spraypainting. The only thing I found to work well was matte gray Krylon spray paint. It leaves a waterproof and UV-resistant seal, and once cured it wasn’t sticky or uncomfortable to wear. I found that any amount of gloss in the paint left the case feeling permanently sticky.

Iterating on the PCB

I ended up with nine versions of the PCB by the end of the project. I switched from a 2 layer to a 4 layer PCB (Signal / GND / VCC / Signal) which helped a lot with routing given the space requirements. I added a BMA400 accelerometer to track step counts (I think it was worth adding it to encourage activity and awareness of activity) and to wake the device up after it’s detected that it’s not being worn. I iterated on component placement to make the final soldering/assembly work easier, and to make the LiPo battery fit a little better underneath the PCB.

I wish I had a better way to connect the battery to the PCB. Soldering the battery leads is pretty stressful, as I don’t want to test out the battery’s short circuit protection. Even the smallest 1.0 pitch JST-SH connector is too big for this application. I considered sandwiching the wires between two pcbs that are screwed together. I didn’t end up doing that, but some way to easily install and remove (and test) different batteries inside these cases would’ve been useful.

Similarly, I wish I was able to configure the layout so that I could use a cable connector for the TFT display instead of soldering the display cable directly to the PCB, which takes time, soldering skill, and good magnification, as the margin between the pins is only 0.35mm.

Custom Glass Fabrication

I learned that a factory in China will make a very small run of your glass with silkscreen for very little, and get it shipped to you within a few weeks time. It won’t be perfect, and it won’t be Gorilla Glass™, but it will be quite close to your specifications and work fine for a prototype.

Once I had the glass, I felt I had everything I needed to begin final assembly. That is, until I discovered…

Surprise! You Need an OCA Laminator

I learned that One Does Not Simply put glass in front of a TFT display. It will look like a first-generation, low-budget Android phone if you do. You need something special called OCA (Optically Clear Adhesive) film, and only a very loud and expensive machine called an OCA laminating machine will do it correctly. If you try without one, you will end up with bubbles and it will ruin the display. This was a problem.

I walked to a local device repair shop, and talked to the owner. It took a while to explain that I didn’t want my smartwatch repaired, and that I was developing my own smartwatch. Once that was out of the way, he told me that he didn’t have access to an OCA machine. His advice was to source a display that already had the glass attached.

That would mean going back to the drawing board on the glass, the case, and the PCB size and shape, none of which I wanted to do to. After a lot of frantic searching, and feeling like this might be the end of the project, I realized that what an OCA laminator was doing was just applying a lot of pressure to squeeze all of the air out from between the OCA film and the glass. I didn’t have an OCA laminator, but you know what I did have? A cast-iron tortilla press. And you know what? After a little trial and error, the tortilla press worked amazingly well! It got 99% of the air bubbles out, and mysteriously, the rest disappeared after a few hours. Crisis averted!

Other Assembly Nightmares

The scale, size, and usage requirements meant the case needed to be tightly compact and as water-resistant as possible. Getting the button size and placement right, getting the placement of the screen, where it was glued to the glass, and where exactly it was soldered to the PCB, all took tedious trial and error. The TFT IPS display was prone to light bleed in corners if it was even slightly pulled or warped, so everything had to line up perfectly to avoid that. I used an adhesive called T-7000 to glue the outer edge of the glass panel to the lip of the case. It didn’t take much to create a strong bond, however ensuring there was no light bleed around the edges also took a lot of trial and error.

Surprise! Arduino is Not Secure

With the prototype assembly pretty much done, I learned that to lock down ESP32-based firmware and prevent it from being read or overwritten, you need to use two things: Flash Encryption and “Secure Boot v2”. I also learned that neither of those things will work with Arduino IDE - you have to use Espressif’s less friendly development framework, ESP-IDF. And most of the existing application code would need to be rewritten using libraries written for ESP-IDF.

I already wasn’t that concerned about IP at that point. The prototype firmware and hardware were both so primitive by comparison to what is commercially available, and it’s serving such a niche market. Anybody stealing IP is already busy copying Apple Watches. I was already leaning towards making the smartwatch open-source and hackable, so this sealed the deal. I haven’t open-sourced it yet, but that’s the plan. Update: the software has been ported to the new Pebble smartwatch and open-sourced here. The original iOS, Arduino and KiCad files from this project have been open-sourced here.

Final Boss Battle: Battery Life Optimization

Most of the watches I assembled had a roughly 3 day battery life, except the one my son wears, which inexplicably has 6-7 days of battery life. 3 days of battery life isn’t bad, but I was finding that if the battery charge dropped too low, it would actually stop charging - something, perhaps the 3.3v LDO or the battery charging chip, was malfunctioning in that state. So for the device to last long enough to send to a beta tester, I needed to figure out how to improve the battery life of the 3 day watches.

I thought that perhaps during development I had changed some of the GPIO pin registers on that one watch’s ESP32-S3, so I wrote a program to dump all of the GPIO registers to understand if any of them were configured differently, but they were identical to the other watches. I tried optimizing the registers so that the ESP32 wasn’t drawing power while sleeping by minimizing floating pins and ensuring all unused pins were pulled low, but that didn’t seem to have an effect.

I also thought that maybe some of the components I used had more variation in resistance than I thought; however, I couldn’t find a drastically different resistance value across any of the resistors in either watch I tested.

I spent days working on this question but ultimately couldn’t figure out why. I made plans for a v10 of the PCB that increased the resistance of several pullup resistors, however I don’t have confidence that will move the needle. Another area that stumped me is how to shut the power off 100% on the device, so that it can remain “off” for weeks or months. Because of the size restrictions of the project and it needing to be water-resistant, I wasn’t able to make the prototype case able to be opened or serviced.

What I Learned

- Hardware development is fun but a steep and rocky hill to climb. You also might end up with a bin problem.

- The gap between even a polished prototype to even a small run of products is enormous. You will find problems that don’t have proven solutions. You will need to get creative.

- Don’t be afraid of designing and building PCBs. You can do it!

- It’s possible to build hardware using US companies like Digikey and OSH Park, but you will be paying 10x to do so. It’s incredible what JLCPCB can do and how quickly and cheaply they do it.

- The retail price of a modern smartwatch is remarkably low for the amount of technology and research and development that goes into it.

- To keep a hardware project going requires a constant updating of parts.

- It cost around $50 in parts to make each watch - most of that was in the PCB production and assembly. With even a little bit of scale, I think it could’ve been reduced to $15-20, but that doesn’t account for the significant final assembly cost.

- This project is proof of how much you can accomplish and learn now with modern AI tools. I would not have been able to get past the initial stages without ChatGPT.

Conclusion

My son and I have been wearing our watches almost every day for 6 months now. He wears his to school. His glass screen cracked a month into the school year, but I was able to disassemble the watch, carefully desolder the TFT display from the PCB and install a new glass laminated display, which has lasted since then. But the time investment to assemble and repair these are steep.

Was this project a success? Well, yes and no. I was able to improve my son’s quality of life at school and allow him to be more aware of his blood glucose and catch lows before all of his alarms go off. The watch passes for a “real” smartwatch. I learned so much about hardware R&D, which presents a very different set of ups and downs when compared to software development.

But I also learned that building a hardware prototype, while difficult, is more like climbing a hill, only to get to the foot of a mountain. Much like software, building the thing isn’t the hard part. The actual hard parts are finding reliable manufacturing and assembly partners, building business relationships, finding backers and funding, engaging the community in an authentic way, building a brand, taking the product to market, and then providing long-term support. Not to mention regulatory challenges like getting FCC certification and potentially FDA authorization.

I have a lot of respect for the people behind the Glowcose and SugarPixel. They managed to do all of the above and build something of genuine value for people in the T1D community.

With the prototype in hand, I reached out to the director of a prominent T1D foundation about the project and was fortunate to be able to meet with them. They don’t fund consumer products like this, but we agreed that the most plausible path to market is the open-source route, potentially turning it into a more general-purpose Pebble successor. But, with yesterday’s announcement that Google has open-sourced the Pebble OS, and that Pebble is coming back, that certainly changes things for this project.

If you’re interested at all in this project, would like to learn more, or if there are things you’re curious about that I didn’t mention, let me know.

Notes

Thanks to Matt Lumpkin for his support and encouragement throughout this project, and his brother Andrew Wyers for sanity-checking my PCB design and giving me the confidence to keep iterating on it.

I reference a few companies in this article - none of them knew I was writing it, I didn’t share it with them before or after publishing, and I was not reimbursed by them.